The cat on the Tehran mat

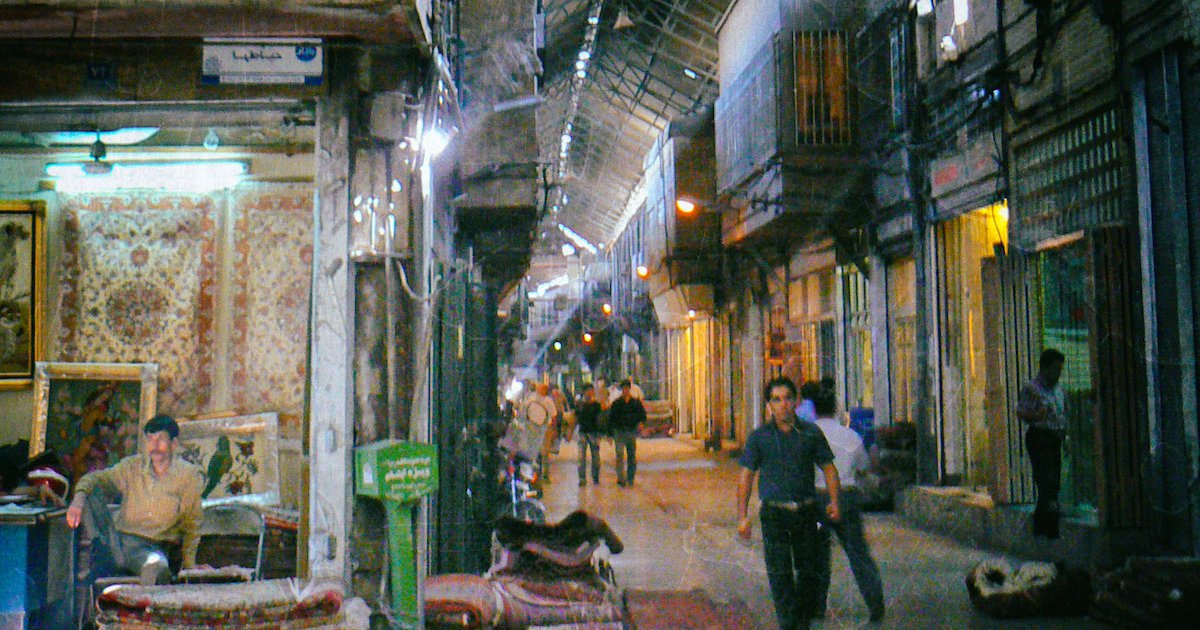

You walk into the room. The first thing you see is that the cat is on the mat. The precious mat you bought at the Grand Bazaar in Tehran, back in what it seems like ages ago. The cat is on the mat –again! – but she shouldn’t be.

The game is lost. Get over it. No matter what you’ll do, you can’t stop the cat from going onto the mat. The cat will defy orders. She will go on the mat, even though she knows perfectly well she mustn’t. And even if she is not on the mat right now, how can you know where she was just minutes ago? How do you know that she will not jump on the mat the very moment you look elsewhere?

It’s tricky. Especially if you are dealing with a mischievous cat, like the one in question here. You can’t do much. You have to catch her in the act. You have to see her with your own eyes. But as we said, the game is already lost. You can’t possibly be there all the time to monitor the mat. The moment you look elsewhere, the cat will jump on it. You know that. Lessons from history.

You could install CCTV, of course. (But then you’ll need someone to monitor the CCTV feed. So, no.)

Or, you could remove the mat. Put it back in the cupboard. Send it back to Tehran. (But it’s a valuable mat and you like it. So, no.)

*

I have been circling around the concept of truth for some time now. Indeed, I concluded my recent Splinters contributions by stating that we need to look at this concept a bit more closely.

So, let’s pause here for a moment. What is it that we are trying to do?

We have a situation. The cat goes on the mat all the time. She shouldn’t. But she does.

We have a state of affairs involving a disobedient cat and a finely woven Tehran mat. We want to know whether the cat is on the mat. We are trying to establish, that is, whether it is true that “the cat is on the mat”. Or, to put it in terms of formal logic, we have the statement “the cat is on the mat” and we aim to assess its material adequacy or truth-value, i.e., its being “True” or “False”.

How do we do that? Simple: we have a look at the mat.

Any discussion about truth involves one or more states of affair and the truth-value of relevant statements. We postulate that in principle there is some truth-seeking procedure that allows us to assess this. In the case of the mischievous cat and the valuable Tehran mat, we only need to have a look. In the case of Axions which might or might not exist, we need to interpret the excess events observed by the XENON1T Experiment.

*

If truth-values reflect the material adequacy of statements vis-à-vis a specific state of affairs, what is truth as such? Surely, you cannot assess truth-values unless you know what this is all about. It’s all about truth, of course – I am stating the obvious. What is crucial, is to recognise that truth, as such, is not the same thing as a truth-value. What is it then?

“Truth” is a frame within which we can consider truth-values. Whenever judgements as to whether something is true or false are involved, truth as such is already presupposed. Even though there is, in principle, a way to assess some statement’s truth-value, truth as such can only be presupposed, i.e., taken as given. It cannot be probed.

This might sound counter-intuitive, but it works in much the same way as on a polling day. The fact that you are invited to cast your vote – for a party, a candidate, an opinion, etc.– presupposes the possibility of elections. Elections is the frame within which you vote. It’s described in a constitution and is taken as a given. It’s not one of the choices.

So, to return to where we started from, we can ask ourselves whether the cat is on the mat or not, and we can have some procedure that allows us to answer the question. The truth-value of the statement “The cat is on the mat” can be established by looking to see whether the cat is on the mat or not. Decisions about the material adequacy of other statements are similar.

Whatever we do, however, we invariably find that there is no procedure to decide the content of truth as such. There is no constitution to describe what truth is. In fact, truth has no content at all. Truth is just an empty frame.

There is a problem here, probably an insurmountable one. Our conception of truth turns out to be more shaky than we would want it to be.

This is not what we expected, is it?

This piece was originally published in the September edition of Splinters.

tinyurlis.gdclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de