Italy’s populist developments after the September vote

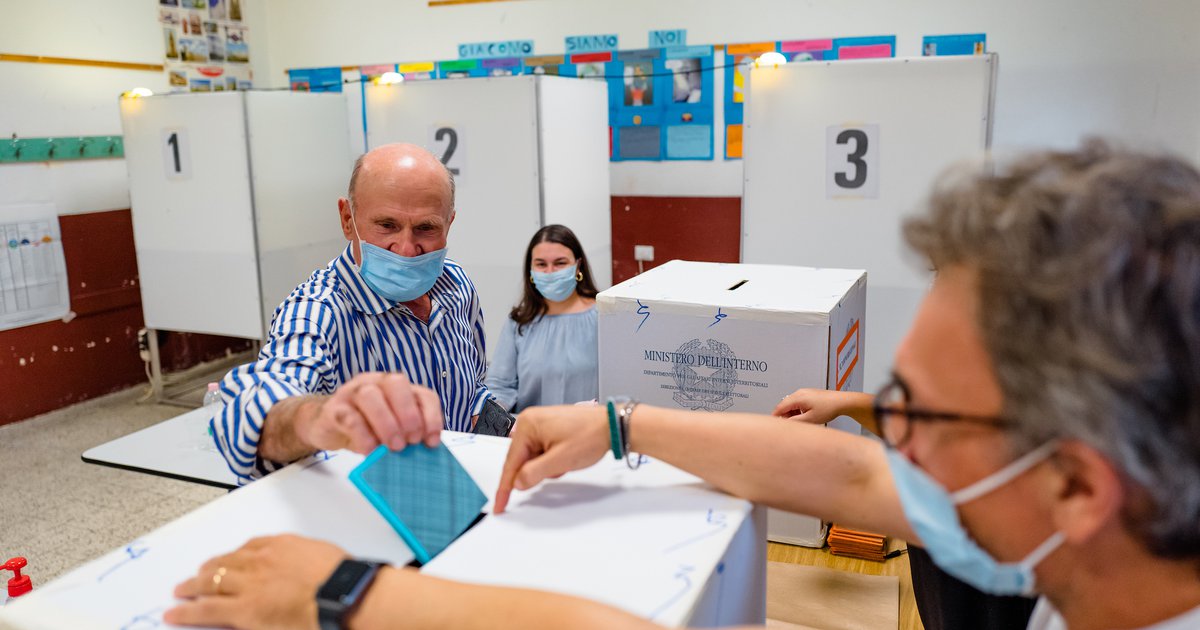

Italy’s electoral comeback after the Covid-19 lockdown was not just impressive because of strict social distancing measures. On 20 and 21 September Italians went to the polls to vote in seven regional ballots, some of which also coincided with mayoral races. On the national level, a constitutional referendum which was planned for March 2020 was postponed and moved to the same dates to reduce chances of contagion.

53,84% of eligible voters cast their ballot, at least averting what had been predicted by commentators as a potential far-right wave. The centre-left Democratic Party, currently in a coalition with the populist Five Star Movement, managed to confirm its hold on Campania and Puglia. As the exit polls poured in, the centre-left sighed in relief as traditionally red territories such as Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna remained untouched.

Sadly, the same cannot be said about Italy’s future when looking at the results of the constitutional referendum – as well as the broader outlook. With a resounding victory of around 70%, the yes vote approved a 2019 law passed by the Chamber of Deputies, but failed to obtain a two-third majority in the Senate. The number of representatives in each of the two Houses of Parliament will now fall by a little more than a third.

The success of the yes campaign, spearheaded by 5SM’s Luigi Di Maio and the League’s Matteo Salvini, is an example of how the pandemic has not necessarily crushed the appeal of populist stances. The speeches guiding the yes camp heavily relied on populist tenets such as people-centrism, the condemnation of elites, and the identification of the yes side with the true popular voice of Italy. In that logic, cuts in the number of representatives seem to have replaced a serious attempt at reforming a turgid system.

Italy’s MP numbers, in fact, was never the cause of legislative backlogs. In fact, for years constitutionalists have advocated for reforms of the electoral law and its so-called perfect bicameralism. This means that both chambers have identical powers and that the government relies on the confidence of both. The reduction in representatives does not address the dramatic consequences of a pinball-style approval or government instability. If nothing else, it puts their burden on fewer shoulders.

Analyses by think tanks and media show that the cuts curtail minority representation for little economic saving, creating disparities between regions on a population basis. The foreseen reduction in the number of MPs elected by a rising number of foreign citizens is one clear case of ill-conceived parliamentary redesign. More specifically, there is little awareness of the tyranny of the majority embodied in this half-thought-through reform: yet it continues to defend its own potential for improvement, based on weak demographic premises.

The reform has no solid economic rationale either. Using a now popular metaphor, the Osservatorio dei Conti Pubblici estimated that savings on net MP salaries will equal 95 cents – the cost of one coffee per citizen per year. Many voters did not question a derisory budget provision, but did doubt representation quotas. It is fair to assume populist arguments found fertile ground among resentful Italians, by equating decades of low-level party politics with a “necessary” rejection of representative democracy.

Paradoxically, the main parties taking a unified stance in favour of the referendum are those which depended on representative democracy to strengthen their legitimacy in the Italian political scene. The 5SM and the League, once fringe groups, profited from their electoral success in 2018 to lay the foundations of their institutional presence in a shared executive. Following their coalition’s dissolution in 2019, the 5SM remained in government, this time alongside the more traditional Democratic Party.

The 5SM might not have dominated the regional races, but it has now won a key battle against the establishment while being an active member of it. At the same time, the League did obtain its own personal trophy, as regional governor and list ally Luca Zaia won another term in Veneto with 75% of the vote. This brings to 14 the number of regions administered by a right-wing coalition where the League has stakes. The Democratic Party should keep the broader picture in mind.

Both victories are symbolic of the transformational qualities of populist style politics in Italy. In its means and intentions, the regional and constitutional successes recycled key populist techniques and arguments, all the while adapting them to the specificity of a changed political context. The result is a parliamentary layout reduced in scope but charged with the same red tape and inefficacy. Accompanying that is a hidden electoral success.

As Italy gears up for a season of socioeconomic uncertainty and prolonged emergency rule, seeing the victory of a front disappointed with modes of representation is no good news. At a time when the Parliament should play a crucial role in scrutinising government actions, it is instead mistrusted and awaits partial alterations. The populist discourse that seduced voters in the first place will now have to supply a replacement for these exposed weaknesses when the time comes.

tinyurlis.gdu.nuclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de