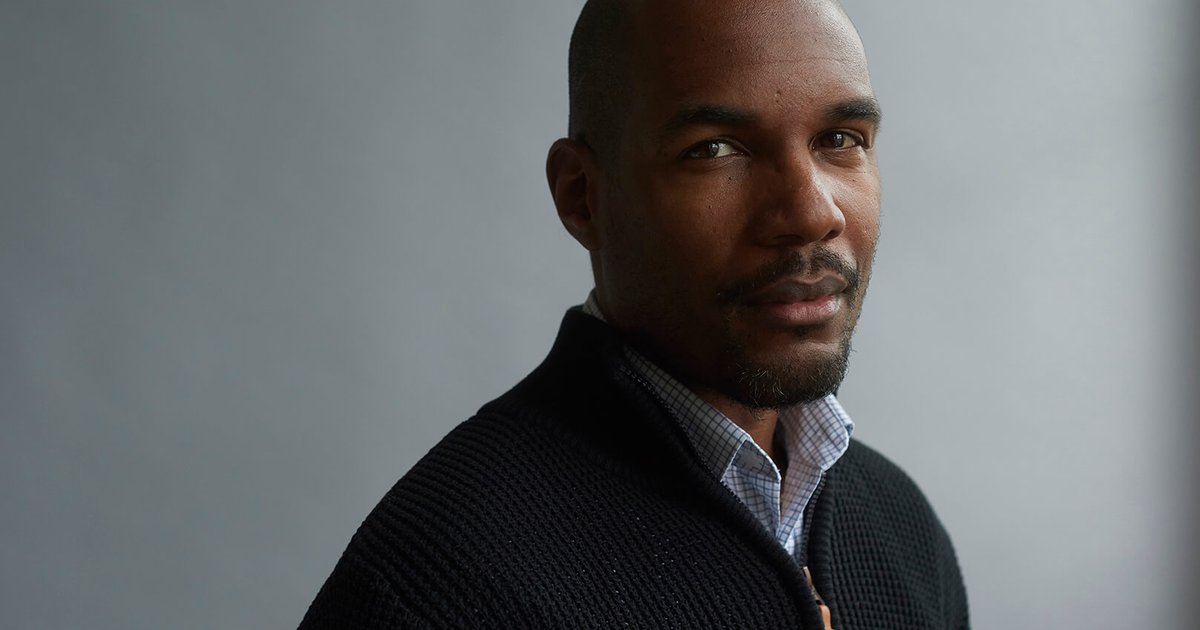

On the latest episode of Changed My Mind, Derek A. Bardowell, author of “No Win Race: A Story of Belonging, Britishness and Sport”, discusses why the mainstreaming of black culture has failed to change systematic racism.

Changed My Mind is produced by Open Democracy in conjunction with The Depolarization Project as part of our commitment to educate citizens, challenge power and encourage democratic debate. Hosted by Ali Goldsowrthy, Laura Osborne and Alex Chesterfield.

Further reading

No Win Race: A Story of Belonging, Britishness and Sport

Remembering Minter v Hagler

Transcript

Derek [00:00:00] I think the thing that I would say probably that strikes me the most is around mainstreaming black culture. And that's what I feel that I have probably really changed my mind around. What I've seen over the ensuing 20 to 25 years is that mainstreaming without a strong racial justice lens, mainstreaming without a level of power and autonomy in those decision making, has really created an even thicker layer of institutional and systemic racist that is so covert and so behind the scenes that I've just really changed my mind about mainstreaming.

Alex [00:00:53] Welcome to Changed My Mind. The podcast where we asked leaders what they've changed their minds on and why. I'm Alex Chesterfield, a behavioural scientist and in a previous life, a conservative politician. You've just heard from our guest today, Derek Bardowell, author of No Win Race and a former director of programmes at the Stephen Lawrence Trust, on how he changed his mind on the mainstreaming of black culture. Before we dive in, I'd like to invite you to sign up for our e-mail newsletter, sign up at depolarizationproject.com to get regular updates in your inbox about Changed My Mind and how to take part in our upcoming show and more. I'm joined for today's episode by my co-host, CEO of a depolarisation project, Ali Goldsworthy.

Ali [00:01:39] Hi, Alex. How you doing?

Alex [00:01:41] And director of campaigns and communications at London. First, Laura Osborne.

Laura [00:01:46] Hello.

Ali [00:01:47] So, Alex, what do we need to know before we hear this interview?

Alex [00:01:50] Well, we recorded this before George Floyd died after spending nearly nine minutes with a policeman in Minneapolis kneeling on his neck. After an outcry the officer has now been charged with second degree murder. Floyd's death, one of far too many, and the ongoing protests around the world made what Derek had to say much, much more important and more poignant. We went back to him to ask the question, had it made him wish he had said anything differently?

Derek [00:02:20] I don't know if I would have said anything differently, given the nature of our conversations and the questions asked, but I'd only reiterate that we're living in a deeply racist system and society, a capitalist system that exploits black and brown people, a capitalist system that exploits our environment for profit at the expense of the masses. The way our institutions and our systems and structures are formulated fundamentally exploits black and brown people and we are existing in a system where those that are in charge fundamentally don't know how to govern a multiracial, multiethnic society, do not acknowledge racism in any way, shape or form. And yet they are tasked or in charge of trying to reform this. They're not capable of reforming this. They they can't even get on the first step of being able to reform any of this. So we always end up in a situation where we're almost waiting for the next incident to happen because tweaking around the edges will not reform this. We're talking about having to really fundamentally dismantle our systems, be it education, be it health, be it the parliamentary system. It needs to be dismantled. It needs to be reformed fundamentally, if we are to gain some level of equity in this society, anything else is just tweaking around the edges. So my thoughts go out to all those black and brown people who continue to not only survive, but thrive and innovate and find ways to deal with this constant hostile environment that we have. To endure to all those who are protesting peacefully. But, you know, the anger and the rage, I completely feel it. I think it's remarkable, unbelievable the way that we carry on and it doesn't overall spill out into the level of hostility that we are faced with on a day to day basis.

Laura [00:05:10] So I was really struck by Derek's comments on the structures and systems that preserve the toxicity of a racist society. And that's been on my mind a lot since we did this interview. He talked about the failure to learn lessons and the lack of fundamental change from tragedies in the past, which was highly pertinent as the US and countries far beyond its borders continue to grapple with the consequences of George Floyds killing.

Ali [00:05:31] Yeah, and listening back to the episode, I have to say that the stories Derek tells and how he explains them reveals the most remarkable patience to me. That was what I came away with thinking, you are more patient than people deserve.

[00:05:32] Yeah, and listening back to the episode, I have to say that the stories Derek Towers and how he explains them just real, their most remarkable patients to me. That was what I came away with, was just thinking you are more patient than people deserve.

Alex [00:05:47] With that in mind, let's hear a conversation with Derek. We'll regroup afterwards to digest some of what he had to say. And share our recommended reading for those interested in delving further into the topics around race and identity that Derek raises. I should say, everyone is recording this in their own homes. There is some chance we may be joined by some unexpected small guests aged between three and twelve.

Alex [00:06:19] Derek. Welcome. I'm really excited to have you on. Your book, No Win Race, looks at some big questions around race and identity in Britain, as well as the unhelpful media narratives that surround sports and its black players. Can you tell us what you found or what your stories, what your stories are?

Derek [00:06:36] Well, the stories found me really because I watch sport when I was a kid, too, like anyone to enjoy sport. I didn't really feel that it would suddenly start to reflect some of the more negative things that were going on in my life at the time. So when I was a kid, I grew up in Newham in East London, and racism was something that was quite an everyday thing for us, for black people, from shopkeepers calling the police and asked to stop and search two old ladies clutching their bags in your presence, you know. That was my everyday reality as an eight, nine, ten year old growing up. So I watched sport because, you know, it was meant to be escapism. But then when I'd watch sport, I would suddenly see lots of black players booed even when they were wearing an England shirt. I would see lots of black players have to deal with the most hostile environment imaginable. So suddenly sport wasn't just something that I enjoyed and something that was entertaining, it was also very, very political. So I would say it really found me. I always say that, you know, athletes don't go into sport to be political. You know, they don't excel at basketball or football or cricket so they can become politicians, but because sport very much reflects what's going on in society and it's also part of the structures of society, clearly, the same disparities that we see on the field of play are the things that we see in our society.

Alex [00:08:14] What's your earliest memory of watching a sport and realising, hang on a minute, this is not right?

Derek [00:08:20] Oh, it was watching the Hagler-Minter fight in September 1980. I remember that vividly because before the fight, Alan Minter, who was a white fighter from I think from Sussex or actually sorry, I'm not quite sure I remember was fighting a black American fire call Marvin Hagler. And before the fight, you know, Minter said something like, I will never let a black fighter beat me. I'll never let a black man beat me, something like that. And this was the height of racial tensions at the time in England, you know? So you just had lots of issues around as we were entering recession around black people being blamed for so many of the social ills. Thatcher had just come into power at the time and was causing a moral panic around black and brown communities and their presence in this country. So Minter saying what he said wasn't helpful. And the crowd was a very jingoistic crowd. It was at the old Wembley Arena at that particular point. Hagler put on a unbelievable display of boxing. He ends up winning in three rounds. But before he gets to even put his hands up in celebration,the crowd just starts shouting racist abuse at him, throwing bottles at him and all of that. And so I'm watching this as the seven year old kid. And in my mind, I remember my dad before the fight saying, who do you want to win? I was like, I want Alan Minter to win because he's English and I was born in England. And then when I saw what occurred afterwards, I was like, wow, is this really happening because of the colour of his skin? And I didn't quite believe it at the time but it scared the hell out of me. Then a year later or a few months later, when there was the Brixton riots, and then suddenly a year after that, most of these kind of incidents with the police became part of my everyday reality. I just remember it just, you know, utterly scaring me. But that was probably the first incident that I can really remember where race and racism really sort of became part of my everyday reality.

Ali [00:10:32] Derek, you used to be a director of the Stephen Lawrence Trust. And after Stephen's murder, getting justice required many, many years of campaigning by Stephen's family and many others as well. And it seemed to me that the police had a real difficulty in admitting that they had got something very, very profoundly wrong. And I wondered what, if anything, you thought had been learnt from that and what lessons could be taken into a current environment to try and help people admit when they've made mistakes and hopefully prevent them ever happening again?

Derek [00:11:12] Yeah, I really struggle with this. And I think one of the reasons I wrote No Win Race was largely because overt racism, the racism that everyone can understand and everyone deplores and everyone hates, you know, that has eased off a bit over the years. But institutional, structural and systemic racism has stayed pretty stagnant. In fact, it's probably not improved on the whole in the last 30, 40 years. And I guess when I reflect on the Stephen Lawrence case and again, you know, Doreen Lawrence didn't have full justice. So not only did it take 20 years for her to get some justice, it still wasn't full justice. And we still cannot even know what level of damage and harm had been done during that time. The difficulty with what has been learnt is that for someone to have that level of resilience, to campaign for that long, just to get partial justice shows immense courage on Doreen's part. But it also says a hell of a lot about our systems and our institutions and how poorly they perform when it comes to racism. No one in those initial positions loses the job because of racism, because people cannot admit that racism even exists. And when I reflect back to the early 80s, and maybe because there was so much overt racism, we could have open and honest conversations about the impact of racism on black and brown people in society. Whereas in 2020, people can't even have that conversation. They're struggling to even you know, people even say to me, does racism exist anymore? You know? So I don't know how much has been really learnt because the structures and the systems, those that preserve this this toxicness of our society hasn't really changed. And because that hasn't changed, I'm really reluctant to say that there has been any learning because if there had been, then we would have seen some quite fundamental changes in our Metropolitan Police, in the police system and policing of black and brown and working class communities. But we would have also seen some fundamental changes in most of our systems. And I don't think we've seen sufficient change in, you know, since the Macpherson report.

Ali [00:13:45] I think, unfortunately, you're probably right, and I'm very struck by what you said about how much easier it is for our brains to process and remember the heroes which in this case is Doreen Lawrence and the Lawrence family, rather than the villains, which in many cases is ourselves. And we all have a stake in, in effect, creating it institutionally racist society. And it's that's the very difficult. And people gloss over it.

Derek [00:14:13] It's a very difficult thing for for people because everyone's complicit. I come back to some of this stuff starts with acceptance, acknowledgement and healing and sort of understanding the roots of some of this. And, you know, I always strike a level of optimism around some of these issues just on the basis that, you know, this isn't like it's in people's bloodstream, like you're born. This is this is part of how we grow up and our socialisation, our environment, our opportunities, our access to health, leisure and all of those things that make up a healthy society. And so much of how we live and how we communicate and how we relate to each other isn't particularly healthy in this society. And racism is a part of that, it's a fundamental root of that. But it's part of a kind of wider lack of happiness, dare I say, that we seem to be living in our current society.

Laura [00:15:23] I was really struck when I got to the end of the book, actually, when you were striking that sort of cautious note of optimism, but also just making that sort, that frustration really clear that, you know, it's not just going to happen. You know, it has to be that people get more comfortable with acknowledging black brains, not just black bodies with, you know, proper trust of black people in power. That right to the very top of arly structures and systems, a huge sort of shift and change is needed. What do you think is a feature of kind of parity, all levels in sport and a sport as a reflection of that in society?

Derek [00:15:59] Yeah. I mean, you guys are some big questions.

Alex [00:16:06] You know, I was like, I'm so glad I'm not Derek because I'd be like, what a big, big question.

Derek [00:16:16] It is absolutely fine. I mean, one, there's no easy answer. No answer that I would give is going to be sufficient enough, is going to be adequate enough. But one thing I would say is that we need a definite change in our leadership. And I've always said that we are in a society that is a multi ethnic, multicultural society, and we need to have people that are in power across the board. And we're in a global society, you know. So you need people in power fundamentally that really understands it understands that has a track record in it with greater diversification. Now, some of the people that I've been fortunate to work with over the years, who I think are absolutely amazing visionary people, they give me faith. They give me optimism because they're the ones looking at alternative economic systems. They're the ones that's looking at how you support those that are closest to social issues, to access the type of opportunities to have power to ensure that no community is left behind. I know that there were people that given that opportunity or given access to opportunities and power, could do some amazing things if they were able to break the structure. But we were in a capitalist system that extracts from black and brown communities, that extracts from our natural resources, and it basically preserves power for a very few people. And part of their game is to divide and and rule against the majority of us, whatever our skin tone who do not benefit from this society. But their game is to ensure that we will never be able to unite with each other and find the commonalities of our struggles to try and overthrow this particular system. So I do think I would like to think there would be an awakening with the Covid 19 outbreak because life is going to change and we are going to have to rely on each other a lot more. And the existing disparities that occur in society will widen as a result of what's happened with Covid 19. We know those that are most vulnerable because of societal impacts are the ones that are suffering the most during this outbreak. So I'm hoping that people realise that there were more commonalities in their struggles and that actually it's a few that are really benefiting from the way that the systems really extract from working class folk, black and brown folk, indigenous folk and those that exist on the margins.

Alex [00:19:26] Derek, how much do you think that Covid will act as a catalyst for greater unity? Or do you see actually in the end, it's going to be more divisive?

Derek [00:19:33] So what we're probably now two months, maybe 10 weeks into lockdown? And I've spent a long time on the phone with many different people around this. And I'd be interested to hear your perspective on this, but what was mass panic for the first month has quickly become normalised in terms of we've become desensitised to some degree to the horrific level of deaths that have occurred, which I find still utterly horrifying. And this rush to get back to how things were. And it feels like, no, surely, surely people can't just try to go back and be on rush hour trains and, you know, things like that. But I can see it happening. And that's quite startling to me, because if ever there was a time when relationships between people should become stronger and where how we support each other and how we look out for each other and how we are more of a community, I would have thought this would be the catalyst of this. But then I also think to myself, we've been fed 40 plus years of of self-interest from the British government and successive British governments. We are taught and grown to to be in competition with each other. We have grown to to be individuals. Our community is our small circle and our wealth. And in trying to iron that out of people, I don't know if this is going to be the catalyst. I would have thought it would be because it's so horrific and so stark and so, you know, in our face. But I don't know whether that's the case. And I always use this this comparison. Remember when the Covid outbreak started and, you know, there's lots of horrible press about people hoarding stuff and people going into shops and buying loads of toilet paper and loads of stuff that no one could get it. And lots of people sent me Whatsapp messages saying 'people are horrible' and all of that. And I was taking this view that, you know, one, if you've grown up in a way that's about self-interest, then fundamentally your mindset when a disaster like this happens is going to be I'm going to get as much as I can, but I still think people are generous in their spirit. So they'll hoard and get stuff. But if someone asked them for it, they would probably give it away. But this mindset shift would be if this happened again, people wouldn't hoard. They wouldn't take and then give away at the point when they know that they're safe. But they would just have enough faith to know that others might need that. And I would love to see where that mindset shift would change, but I'm not optimistic about that. And given that we are in, you know, climate crisis and that this will probably not be in my lifetime, the last time something like this will happen, I am just hoping that the lessons learnt this time round will really start to stick in terms of looking at real fundamental change. Different alternative economies and different ways in which we live with each other and for each other in the future. But I don't know whether this will actually catalyse that at all.

Ali [00:23:32] I share your pessimism. Actually, I think it's going to reinforce divides. And if you take your example of if there was another epidemic, if you find yourself without things this time, would you not be more likely to go and get things? I don't think it's always necessary, just selfish. I think sometimes as people wanting to protect their family. That's probably how they'd frame it themselves. And I get it. There was a great article and we'll link to this in the comments, there was a fascinating piece I think it was in that The Guardian where they were talking to a woman who was had been over buying food. She'd be struggling with financially. And just like I don't want my kids to be without. I want to protect my kids. And and, of course, I want to and I'll do whatever I can to make sure that they can always eat. And even if that means buying much more than I need to and having to throw out a lot of food. And I was so struck by that that she had framed it in her head about keeping her family safe and the people she loved safe. And I think that's probably likely to become a prevailing dynamic. I don't know, Alex, you might have your own behavioural psych take on that.

Alex [00:24:40] Well, I agree. I think at the beginning, and I'm quite a I guess probably naively optimistic person anyway, I thought, I did feel I do think it's a catalyst for greater unity. A lot of the social psychology suggests that when people do have a common goal or a common enemy, which in this case is the virus, it can heal divides and people come together in the face of a sort of common challenge to to essentially try and fight it. But as as it's unfolding, I am not seeing that. And I'm seeing it as as actually an opportunity to capitalise is the wrong word... entrench? Use? Leverage those existing divides for kind of gain that is not in not in everyone's best interest. So I'm on the pessimistic side of the fence now as well.

Ali [00:25:27] Some cheer, some positivity.

Laura [00:25:32] So I've got an optimistic note for you, if you'd like one, which is I've been talking to quite a few business leaders in my day job. And one of the things that's really struck them through the crisis is the realisation that they don't normally talk to all of their staff. So thinking about like the structures and things and hierarchies within businesses, that this is the first time they've had kind of equal access to everybody who works in their businesses. And that that's given them loads of insight into how young people are living their lives, what matters to them, you know the difference in living standards. If you're in a room share or flat share compared to, you know, if you study and you got in or, you know, say I've been sort of mildly optimistic to hear how much thought they they've now given to what the future looks like for their workforce. I've not really heard people talk about it in that way quite so much before. So there's there's one optimistic thought.

Alex [00:26:34] Derek, when is the time that you changed your mind on something? What was it and why?

Derek [00:26:39] What was it and why? So the first thing which I dip in and out of it is around philanthropy, money and whether that really can be something that heals. I've worked in philanthropy for over a decade. And I've seen really good stuff occur as a result of money spent wisely to amazing people, projects and communities and stuff. But I kind of sway in and out of that one depending on how the mood takes me, I could be really positive about it. On the other side, I could be money can't heal. We need to dismantle it. I think the thing that I would say probably that strikes me the most is around mainstreaming black culture. And that's what I feel that I have probably really changed my mind around. And what I mean by that is this, you know, when you go back to the 80s and 90s, it was very much an era of multiculturalism, which was really around. There was just resource for black and brown communities to be able to generate things for their community because it wasn't being represented in the mainstream. And I kind of grew up in that era, you know, as a teenager in the 80s than it was 20 year old plus in the 90s thinking that these mechanisms, be it black newspapers be it black radio stations, charities serving the black community. And our communities were absolutely amazing and brilliant. But the aim was to try and mainstream most of this stuff. So the whole idea was at some point we would be able to be represented in the BBC and equity would be in the BBC and it would be in politics and it would be in all of our institutions. And once we had been able to, for want of a better word, integrate within those particular systems, then all would be well and fine. And so that was the aim. And that was for me, I guess, something that I'd grown up with, which was, you know, I'm trying to write for The Guardian. I'm trying to write or be on the BBC and trying to get into those mainstreams spaces. And then this is also a time in the mid 90s, of course, when I would say that black Britons were really started to embrace their Britishness. So where that notion of I'm African Caribbean was starting to move towards I'm black British. So there was a kind of ownership with it and there was a kind of integration that was going on that felt really, really positive. And I kind of got really swept away with that. But what I've seen over the ensuing 20 to 25 years is that mainstreaming without a strong racial justice lens, mainstreaming without a level of power and autonomy in those decision making has really created an even thicker layer of institutional and systemic racism that is so covert and so behind the scenes that I've just really changed my mind about mainstreaming as such. Which doesn't mean that we shouldn't be trying to get into those places and infiltrate it. But I think it's the how we infiltrate it. And I think the piece that says so much of those independent organisations and initiatives that we had at the particular time died once we started to mainstream, you know, because people started to say we don't need that anymore because there were more black people in the BBC. There are more black people in mainstream media. So we don't need that or what we were doing was revealing some of the work that we were doing, and then you would have lots of white organisations or white led organisations that would co-opt or misappropriate black culture. Take it, monetise it and do an Elvis Presley with it on rock n roll and essentially be able to create of revenue stream from it that killed some of the black business because they were largely the safer option for the white mainstream. So you ended up by mainstreaming our work. We were no longer the voice of our own communities anymore. We were essentially having narratives written on our behalf by white press people and by white media people and by politicians that was not reflective of our communities and what we wanted. So for me, I think I grew up with that notion that mainstream was the main thing that we needed to do. And seeing how that's been abused over the last 25, 30 years, I think I've just drawn back on that and just said, yeah, we, we do need to mainstream, we need to be in those, those spaces. But we self-determination is really fundamental to ensuring that those mainstreams spaces and places are really holding up their end of the bargain. And as I've said, the mainstreaming of black culture has fundamentally in the way that it has been done over the last 25, 30 years, has fundamentally ruptured that level of self-determination that we've had in our communities.

Laura [00:32:40] I was really struck by that, actually, listening to Just Cause when you were talking, I can't remember who your guests were, but about all of the organisations that ceased to exist during that period of time and who are needed now at but not funded now.

Derek [00:32:54] I know so many stories of organisations, good organisations, strong organisations that either no longer exist and a really fundamental now. So one thing that I should qualify this is that, you know, I went to school. I was really lucky in that I had some absolute kickass parents that looked after me and were just absolutely the best parents, absolutely imaginable, because when I graduated as a 21 year old, I didn't get a job through a formal job interview basis until I was 29. So I was essentially eight years unemployed or unemployable. And when I say it was how bad it was, I would go in for an interview. And the white person sitting behind the desk would turn around as I walk through the door and say we're no longer hiring, which sounds like something from the 50s and 60s. And this was the 90s.

Laura [00:33:57] I was really shocked when I read that in the book, Derek, I was it was just like, oh, my God, that's horrific. Because you think of it as a time that's gone. Not something that would have happened within your lifetime.

Derek [00:34:14] I mean, I it's it's absolutely crazy. So you always know that. I mean, I've done interviews before where I know that the person's not going to hire me and they're just going through the motions because they don't want me to report them or things like that. So I've experienced that many occasions. And, you know, you learn how to deal with it. But when you actually have it blatantly in your face and as someone that for me, I felt like, you know, I've gone to college, I've gone to university, I've done everything the society and I and I worked through through university as well. So I had experience coming out, you know, that I've done everything that society has taught, told me to do, and I still cannot get work. It's one of the most disempowering things imaginable. It makes you really bitter. You know, if you ever spoke to a moment that they could tell you what it was like as a young 20 year old and stuff, you know, so but I was fortunate because I had, you know, a wonderful family, a strong family. But the thing that really rescued me is that there was black businesses and organisations like The Voice newspaper, like Power Moves, like Jetstar that were able to take me on, often informally. To be able to build up my work, my resumé in a way that mainstream organisations didn't. And given all of the disparities that we know still exist, which came out of the race disparity audit, you know, unit that was commissioned by the government two, three years ago. We know the disparities still exist. I still had a pipeline in the 90s that enabled me to progress in my career. But so many of those organisations in that channel has now gone through mainstreaming. It means that a lot of our young people just do not have a pathway whatsoever to be able to get up on the ladder. And that's the bit for me that's really, really tragic that we don't have this thriving independent scene. And this is not just about race. This is on so many different levels that so many things have been sucked up by mainstream organisations. I liken it to about 20 years ago when sort of the five major record labels pretty much bought up every independent label imaginable. And pretty much if you were trying to get a deal or trying to do anything in the mainstream in music, you know, it was either Virgin or Sony or Universal, one of those four or five big magnates. That's how it feels, you're really on the margins looking in and you can't get in because of what's happened over the years. So that part of self-determination really needs to come back because that is a huge pipeline for many people in our communities to get a step up into the ladder, but also to be able to have the confidence to be themselves once they get into those mainstream spaces.

Laura [00:37:23] And we wanted to ask you as well, Derek, we do ask everyone, who would you really like to hear from about the time they've changed their mind on something?

Derek [00:37:34] Wow.

Laura [00:37:36] Another big question. But could be anyone, they don't even have to be alive.

Ali [00:37:45] I'm worried about the questions Derek's going to ask us now.

Derek [00:37:48] No. I mean, I'll come to questions to you guys in a minute. I mean, I'm really curious to know what lies behind Barack Obama and what really happened in the White House during all of those years as a black man with that level of power and what power really means. I mean, it's an obvious one. But, you know, obviously what we get from him is a kind of conception of him now. And what we don't know is that the reality of what that is and I don't know if we will ever know the reality of what it is to be within those structures and those systems. I mean, I don't know how he got through it, but, you know, whether you, you know, support him, applaud him, or you don't support him or applaud him. Very few, if any black people have had that level of power or access to power. So I am just utterly and will always remain curious about the reality of that situation, the reality of what it must have been like getting up and what that has done to change any of his conceptions or his politics or his viewpoints to what he held when he first got into office. Because I don't see how an experience like that couldn't change some quite deeply fundamental things about about you as a person.

Ali [00:39:21] You're the first one to nominate him, actually, and I'm not so confident my ground on where he talk about race. But he has talked quite openly about how he changed his mind on gay marriage before he came into office and the role that his kids actually had in changing his mind about that. But we might well go and do some digging and people will find it in the in the links afterwards. We sort of mentioned before we started, Derek mentioned before we started recording, that he had questions for us, which is what's now making my palms slightly sweaty. Having dealt some very fairly big balls at you. That's a terrible expression, edit that.

Derek [00:40:02] I am always curious about how to communicate about race and racism and knowing that you guys or some of you are behavioural scientists. I'm just curious what you guys have encountered in terms of really trying to communicate either the impact of race and racism or the conception of, you know, race is a social construct. We know this, but people don't treat it as a social construct. They still treat it as some natural hierarchy that exists. So I just want to know from your perspective or from whatever research that you've done, what you found out in terms of communication about race or what you've seen from communities or research that you've done in the past.

Alex [00:41:01] I don't know the literature around specifically on communicating on race. And I wouldn't want to do, I imagine, much the research that does exist and injustice by trying to give it a wrong or crappy, unhelpful answer. But I guess what we have found out from research on polarisation, I guess more generally from behavioural science, is that often and actually this actually chimes with some of the research I did at Which and also when I was at the financial regulator, that's where I met Paul, the FCA, is that often policymakers and regulators and politicians will want to communicate with facts and statistics and data and evidence, and they are convinced that if you just give people more information that they will change their minds and they'll come round to whatever that their perspective is on a particular issue. But that really does not work. And actually, what people do respond to, and it chimes with what you were saying in your book as well, is stories. It's narratives. It's about people's personal experiences, their stories. Where they come from, what they've found. That's what really resonates with people. And you can see some of this I guess, in the charitable giving literature, and it's called the identifiable victim effect. So where were you highlights how just, you know, one person. So, for example, a child has been impacted by and I don't know, for example, taking one example from famine. That prompt encourages charitable donations much more than, for example, saying on aggregately, there's millions of children being impacted by famine. Just highlighting the story. And I guess the plight of one one person encourages us. I guess I think because we can relate to them much, much more. It becomes real. And again, we start to relate that our own experiences or people that we might know or think about all of our own children in that situation, much more than I guess, you know, millions of people that become quite faceless. And I think, again, it resonates with what you were saying beginning about how actually when normalising to a lot of the Covid, the numbers are in the thousands. But you just become normalised. But actually, once you hear about somebody that's close to you, or you can relate to, or you know them. It suddenly then starts to really hit home. So I guess that's a very long winded way of saying I can't give, but I'm actually very interested in it and I will look into and come back to you on it. I'm interested, but I don't know specifically on communicating around race, but there might be some read across from that broader literature.

Ali [00:43:36] The only thing that's probably worth bringing out there is that whilst it's shown that it does lead to greater donations or I'm not as am a year or two out of date in my reading on it, like there's also quite bigger systemic problems that comes from reinforcing perceptions of particularly black people. And of Africa more generally, that is full of famine. It can backfire quite badly. I mention it because it's very funny. We'll link to it. But that was quite hilarious thing that people, black people in Norway did, which was a charity song called Africa for Norway when they found out that they were having some slight social problems, that they could all sing for them. And I just think it beautifully makes the point about how patronising and occasionally ridiculous it can seem when there are. Yes, there are issues within Africa, of course, in terms of economic development, but quite a few are thriving now. So, like, Rwanda's got a better GDP than Wales per head and things like that. And that becomes quite challenging for people with their perception. So, yeah, I'm always slightly careful about the imagery that I use when I'm campaigning as a consequence.

Alex [00:44:47] Derek, thank you so much. This has been fascinating, I now want to go away and process this for at least the next two weeks. Thank you.

Derek [00:44:55] Thank you. Thanks for having me. I really appreciate it.

Alex [00:44:58] Pleasure.

Laura [00:44:59] You're very welcome.

Alex [00:45:06] So, Laura, what was the key takeaway for you from that conversation?

Laura [00:45:11] I think particularly given what's happened since, it's spurred me to think a lot about racism in the UK, including Derek's own experiences. And I was struck by what he said about the 80s. Racism was so overt there was a clear conversation about it and how now where it manifests a bit differently. People just in some ways haven't been having that same conversation, but perhaps they should have been all the way along. And that's been brought into sharp relief over the last couple of weeks. But I think, sadly, it shows that things haven't moved on nearly as much as we might like to think they have.

Ali [00:45:41] Yeah, and like a lot of people, I think I've been on a bit of — or like a lot of white people, I should say — I think I've been on a bit of a journey around racism. A bit like sexism. You know, I was brought up to believe that they passed legislation, the Race Equality Act and things like that. And that really that that was going to try and help solve the problems, that it wasn't really a norm or super widespread. And I did. I grew up in a very white area of rural South Wales, is not known for its ethnic diversity. But even with the Macpherson report, my instincts were to want to believe the best in people and not to believe that they or as a society we could be institutionally racist and that that was my bad. And I suppose it's something that I've changed my mind about. Partly thanks to the eloquence of people like Derek and often the humour with which they've made their point. And I really think we should continue to give them the floor as much as we can to hopefully change a few more people's minds about it.

Alex [00:46:42] I feel the same and Derek's position feels right. So like him, I celebrated black voices becoming part of the mainstream. But sometimes you need your own space too.

Alex [00:46:55] So that's that's all from us today. Thank you very much for listening to this episode of Changed My Mind. If you liked what you heard, don't forget that we have a full back catalogue of fascinating interviews with leaders. You can find them all by searching "Changed My Mind" in your podcast app. We'll be back next week with a new episode chatting to a leading author and lawyer about the role of tech and what it means when it takes over the world for our democracy. Make sure you're subscribed in your app or to our newsletter at depolarizationproject.com. So you are the first to know when it comes out. Thank you to Open Democracy for their support of the show, to Caroline Crampton, our wonderful producer for editing, and Kevin McCloud, whose Dreams Become Real is our theme music.

tinyurlis.gdclck.ruulvis.netshrtco.de

مقالات مشابه

- 27 جدید COVID-19 مورد اعلام کرد به عنوان داکوتای شمالی می افتد کوتاه از تست هدف

- یونان آسانسور خود را مستند در هتل, استخر, زمین گلف

- گامهای مستقیم برای مواد شیمیایی از آرزوها

- استخر بادی چگونه میتواند باغچه شما را زیباتر کند؟

- Top 10 نکته با برج خنک کننده

- شرکت صادرات و واردات کالاهای مختلف از جمله کاشی و سرامیک و ارائه دهنده خدمات ترانزیت و بارگیری دریایی و ریلی و ترخیص کالا برای کشورهای مختلف از جمله روسیه و کشورهای حوزه cis و سایر نقاط جهان - بازرگانی علی قانعی

- مهره مار - نامـوس کفتـار - مهره گبری

- آفتاب سوخته برچسب سقف ماشین نقره ای: ارتقاء ایمنی و زیبایی خودروها

- در Nixon کتابخانه Pompeo چین اعلام نامزدی یک شکست

- Grand Forks school plan brings options and, for some, relief